Imagine you’re walking down your city’s main street. If you’re 35 years old, there are cafes, shops, and banks. But if you’re 56 years old, the banks are missing.

This could happen on the digital main street, where a handful of big tech companies provide the main platforms for finding information. As bank branches close down and online personal finance takes over, it’s becoming more difficult to see if groups of people are being excluded from financial opportunities in the digital world, even though US federal law forbids discrimination on the basis of age, race, gender, national origin, and marital status.

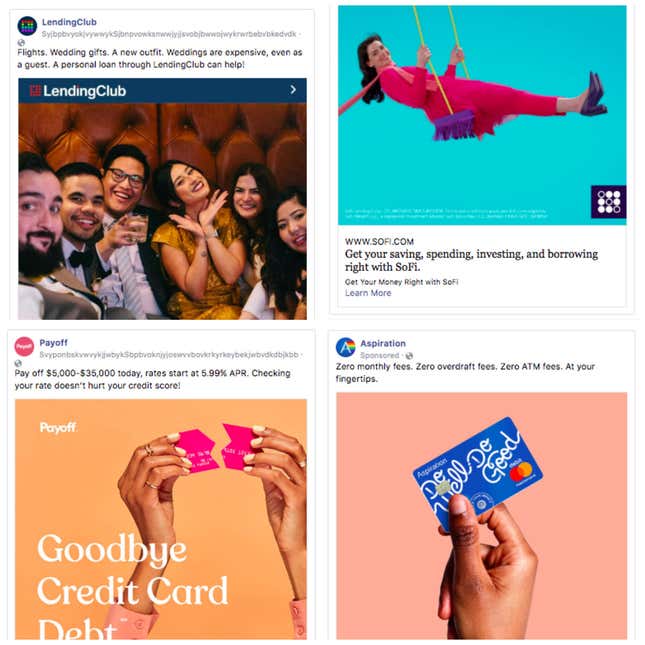

Facebook is one of the internet’s main streets. Together with parameters set out by marketers, its targeting tools and algorithms determine which job and financial ads millions of people see. Earlier this year, the social network settled lawsuits with civil rights advocates alleging ad discrimination, and it has been overhauling a system called Lookalike Audiences as it applies to job, housing, and credit advertising. Yesterday, Facebook was hit with a class action lawsuit alleging age and gender discrimination in the financial ads it serves.

Targeting ads with Lookalike Audiences is pretty much what it sounds like: Advertisers can upload a list of their best customers and Facebook finds users like them based on a set of categories identified by algorithms. If the list it is given is full of white men, it could very well show ads only to a bunch of other white men. The trouble is identifying which categories and characteristics the algorithm has selected.

“It’s a black box,” said James Robert Lay, CEO at the Digital Growth Institute, a marketing firm. “It’s using a slew of information we don’t have access to.” He said this type of targeting was used by the financial industry for years.

Even if there’s no intention to discriminate, financial ads are different from other kinds of advertising because they represent a chance to prosper and participate in society. That’s why an algorithm that systematically excludes protected categories like age and race from seeing credit ads could be unlawful under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). “We know from research that Lookalike Audiences can reproduce those protected characteristics, including gender and age and ethnicity in the new audience they create,” said Aaron Rieke, managing director of Upturn, a nonprofit research group, and a former attorney at the Federal Trade Commission.

Quartz analyzed a set of Facebook ads that were shown to a group of volunteers, as part of a project with The Globe and Mail newspaper. The ads include an explanation, provided by Facebook, about why a person was targeted: The financial companies had asked Facebook to show the ads to “people who may be similar to their customers.” Put another way, they used Facebook’s Lookalike Audiences feature to target the ads.

These financial companies used Lookalike Audience targeting this summer, before Facebook began enforcing substantial changes to these types of advertisements on its main ad management platform in August.

In June, San Francisco-based SoFi ran Lookalike ads for credit that were targeted at Facebook users in the US between the ages of 22 and 49. The company said ECOA applies to discrimination in the application process, and that its credit applications are widely available on SoFi’s website. SoFi said its Facebook ads are for “brand awareness.”

“We send different ad messages to different people so that we are sure to deliver the right message to the right person to best meet their needs,” a spokesperson said in an email. “We pride ourselves on adhering to our extensive regulatory environment, as it serves the most important role: protecting our member’s interests. We’ve taken great strides to ensure we always are compliant with any laws regarding targeting on Facebook.”

LendingClub said the Lookalike ads that Quartz reviewed were part of a test that started in February and has since ended. The company said its ads on the platform were for “brand building,” and not for direct response loan applications.

“Our Facebook spend is less than 1% of our overall marketing budget,” said a LendingClub spokesperson. “We are completely committed to fair lending practices. Researchers at the Philadelphia Fed have analyzed our data and concluded that we’re lending in more areas where banks are closing their branches, we’re improving pricing and the quality of credit decisioning, and increasing financial inclusion.”

Aspiration and Payoff didn’t reply to requests for comment.

“It’s different than selling shirts or underwear,” said Peter Romer-Friedman, counsel at Outten & Golden in Washington and one of the negotiators in the Facebook settlement. “You’re selling credit or jobs or housing, which determine peoples’ outcomes in our society in many ways, and their ability to prosper.” His firm filed a class action lawsuit yesterday against Facebook, alleging years of age and gender discrimination in financial ads.

A spokesperson for Facebook said the company is reviewing the complaint. “We’ve made significant changes to how housing, employment and credit opportunities are run on Facebook and continue to work on ways to prevent potential misuse,” they said. “Our policies have long prohibited discrimination and we’re proud of the strides we’re making in this area.”

“Ethnic affinity”

Concerns about discriminatory ads on Facebook aren’t new. In 2016, investigative news website ProPublica showed that Facebook’s tools could be used to avoid showing housing ads to people based on their interests, backgrounds, or “ethnic affinity.” The social network said that its policies barred discrimination, and it was building technology to catch problematic ads and provide more education for customers. The following year, ProPublica reported continuing lapses in Facebook’s claims, showing that the social network would quickly approve ads that could be discriminatory.

In 2018, Facebook was sued by civil rights groups, including the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA), for allegedly discriminatory ad practices. Facebook began a civil rights audit that year, led by Laura Murphy, former director of the ACLU Legislative Office.

The lawsuit was settled this earlier this year, in March, and Facebook agreed to make changes to its ad platform. The NHFA said the settlement resolved claims alleging that Facebook unlawfully enabled advertisers to target housing, employment, and credit ads to users based on race, color, gender, age, national origin, family status, and disability. The case also challenged Facebook’s Lookalike Audience tool.

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg said advertisers for housing, jobs, and credit would have “a much smaller set of targeting categories to use in their campaigns” as a result of the changes, and that the company already prohibits advertisers from using its tools to discriminate. All advertisers must certify Facebook’s non-discriminating policy. The company said it was making a tool so users can view all housing ads in the US.

“This is an area where we believe we’re making strides in the advertising industry,” a spokesperson said.

In a June progress report, Facebook said it was changing its targeting system to no longer allow job, housing, and credit advertisers from picking out “interests” that tend to be associated with protected categories (interests like Spanish-language TV, for example, could be used as a way to target or exclude Hispanics). Location targeting was broadened so that individual zip codes could no longer be singled out, and Facebook said it was talking to outside experts to study bias in algorithmic modeling.

In August, Facebook announced its alternative to Lookalike ads on its main ad-buying interface. It’s called Special Ad Audience and uses online behavior instead of categories like gender or zip code. Although Facebook worked with civil right groups on the changes, some legal experts and researchers are unconvinced the modifications will eliminate discrimination.

The only way to know for certain whether the algorithms discriminate against people is to compare the input data with the output data, according to Till Speicher, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Software Systems in Germany who researches online advertising. “If an attribute is rare in the source it will be rare in the results,” he said.

Cathy O’Neil, a mathematician, said Special Ad Audience targeting is unlikely to remove algorithmic bias. “It’s less of a direct signal than demographic profiling directly, such as female versus or male, or black versus white,” said O’Neil, author of Weapons of Math Destruction, a book about algorithmic bias. “But it’s of course correlated. People in the same class or ethnicity tend to have similar habits. It’s a backup proxy for those kinds of issues like class, race and gender.”

Who, what, where

Quartz’s reporting is a snapshot of ads shown to volunteers, meaning it doesn’t capture the full advertising campaign for any advertiser. It’s conceivable that a company could exclude protected groups when using one type of Facebook ad targeting, but those groups could be included in the overall campaign. Direct mail, for example, is still a major means for advertising personal loans.

There are ways to see what ads you aren’t shown. Anyone, including people who don’t use Facebook or one of its family of platforms, can search its ad library to see marketing material, even if it wasn’t targeted at them. The questions raised about Facebook’s ad practices are also relevant for other tech platforms like Google, which hasn’t yet been subject to as much scrutiny.

When Facebook rolled out changes to ad targeting for financial firms at the end of August, it was a shock to digital marketing companies. Meredith Olmstead, CEO and Founder of FI Grow Solutions, said all the financial ads her company was running for clients got shut down in September. The company’s clients typically look to FI Grow to run their campaigns.

“Every kind of ad for financial institutions has been impacted,” she said. “Every single one of our clients uses Facebook ads. We’ve actually don’t work with anyone who doesn’t use Facebook ads.”

She said there are reasons to use Facebook targeting that have nothing to do with discrimination. A product’s ads might use different images for different age groups, for example. The way a company pitches a home-equity loan to a 40-year-old can be different than the way it pitches it to a 55-year-old.

Likewise, a community bank might target only the zip codes where it provides services. Olmstead said it was common to show ads only to the zip code around a bank’s branch, but that is no longer allowed. Under new Facebook rules, those types of ads can’t be more precise than a 15-mile radius. Age restrictions are also forbidden.

Olmstead said her company used Lookalike Audiences, ages, and zip codes for targeting, but didn’t use categories like income, gender, or ethnicity. She acknowledged that Lookalikes were an algorithmic black box. “There’s no insight into what kind of demographic elements are being targeted,” Olmstead said.

Seeing red

Regulators are concerned about financial exclusion because there’s a long history of banks engaged in it. Congressional hearings in the 1970s showed that lenders were “redlining,” or systematically avoiding making loans to certain zip codes and neighborhoods, and excluding non-white and lower-income people in the process. Hearings found discrimination on the basis of age, gender, race, national origin, marital status, and religion, and they resulted in regulations like ECOA and the Community Reinvestment Act.

Cutting people off from credit can be devastating: The businesses that support jobs are likely to abandon areas if they can’t get financing from banks or other lenders, as Willy Rice, a law professor, wrote in the San Diego Law Review in 1996. It can lead to long-term unemployment and blight.

Now that algorithms distribute information, it’s becoming more difficult to tell whether groups of people being excluded, either unintentionally or by design. The rules protecting access to credit and jobs may also need a refresh, since they were enacted in an era when bank branches were more widespread and the internet didn’t exist.

“When you take systems like that and apply them to a society that is built on discrimination, the data inputs from the society feeding into the algorithm have the taint of historical biases built into them,” said David Brody, counsel at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “The advertising and technology companies are stumbling through the dark and afraid to turn on the lights to see how many cockroaches there are.”

For example, should advertisements for checking and savings accounts be allowed to exclude people based on race, age, or gender? These aren’t ads for credit, which are explicitly covered by the law. But checking accounts often serve to get customers in the digital door so that banks can sell them loans.

Ally, for example, ran an ad using Lookalike Audience targeting on Facebook that was aimed at people aged 25 to 64. Its financial ad was for online savings accounts, not credit, which likely wouldn’t fall under ECOA.

The company didn’t respond to specific questions from Quartz about its use of Lookalike Audiences. “Any conjecture that Ally discriminates in its advertising is unequivocally false,” a spokesperson said. “We believe any suggestion otherwise would be misleading to readers.”

Quartz’s reporting captures a small part of any company’s advertising campaign and doesn’t prove that discrimination occurred.

“Even more aggressive”

In the offline world, it’s easier to identify discriminatory practices by looking at the location of bank branches.

In 2004, the US alleged that a Michigan-based Old Kent Bank placed its branches in white areas while avoiding black neighborhoods. As the bank expanded, all of its branches were located in Detroit’s metropolitan area but not in the city of Detroit itself, which was mainly black, according to the government’s allegation. As little as 2% of the banks’ small business, home improvement, and home-refinance loans were made in areas that were majority African-American neighborhoods. Old Kent settled with the US without admitting wrongdoing in exchange for agreeing to market more lending in minority neighborhoods.

“One of the practices at issue was a bank not putting branches in predominantly black and Latino communities and not recruiting in those areas, which in turn reduced the number of people of color getting loans and having access to credit,” Romer-Friedman said.

Digital ad algorithms are “an even more aggressive form of that,” he added. “Companies need to abide by the spirit of the law, not just the letter of the law.”