AARP Hearing Center

Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of histories such as No Ordinary Time, Team of Rivals and The Bully Pulpit, has turned to a more personal story for her latest book — An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s.

Her late husband, Dick Goodwin, was a presidential aide and speechwriter with an insider’s seat in the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson White Houses — sometimes a little too close, as during a skinny-dipping policy meeting in the White House pool with LBJ. Goodwin has woven her recollections of those days along with some of her husband’s private writings into a look at America during a time of deep divisions along racial and generational lines. We talk with her about those times and what we can apply to our own divided era.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine. Find out how much you could save in a year with a membership. Learn more.

Your new book, An Unfinished Love Story, is a personal look back at the turmoil of the 1960s that began when you and your late husband (and presidential adviser), Dick Goodwin, decided to go through 300-plus boxes of material he’d saved from his speechwriting days with John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

We spent weekends doing it, reliving a decade. I was stunned by the dimensions of what he’d kept. He was everywhere you’d want to be as markers of the ’60s. He was with Kennedy on the plane [during his presidential campaign] and at the White House the night JFK’s body was brought back from Dallas. He was with LBJ at the great moments of the Great Society, then got involved with the antiwar movement.

What did you find in those boxes?

I knew all the things that had happened to him. His first wife died, then JFK was assassinated. Then Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated, and Dick’s dreams of continuing the Great Society were cut short. But when we went through the boxes, something happened to him. It was almost miraculous. He recovered his sense of joy. Looking back on his life, I think he felt that what he had worked on had mattered.

Did your views on JFK and LBJ conflict?

Dick was loyal to the Kennedys always. It was partly because that’s where his first understanding of public life came from, in his 20s. The Kennedy family was part of his upbringing. In my 20s, I worked with LBJ and became part of his family. So when we talked about those men over the course of our marriage, we often sparred with each other. Some poll would come out ranking JFK higher than LBJ, and I’d say, “That’s not fair. LBJ got everything through Congress that JFK tried to get through — the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare and Medicaid.” And Dick would answer, “Yes, but if JFK had been in office, what would have happened with the Vietnam War?”

You Might Also Like

50 World Changers Turning 50

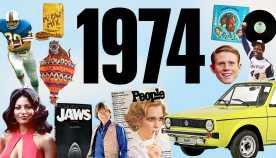

1974 brought us Nixon’s resignation, MLB’s first Black manager, the premiere of ‘Happy Days’ and more

Tiger Woods Connects With Dad

James Patterson’s book highlights how the golf pro worked out at his father’s old military training ground

Tips to Write Your Memoir

From how to get organized to finding support, here’s how to start telling your story

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You