NEW ORLEANS — When a pair of suspects fled a routine traffic stop and shot at a Baton Rouge-area police officer in 2020, DNA at the crime scene helped police quickly arrest one suspect.

But the other remained on the run, until he was arrested for another crime — possessing stolen goods — two years later. Using a “Rapid DNA” machine at booking, the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Office took a cheek swab and connected the person to the previous crime while he was in custody.

This was made possible by what detectives there call a “lab in a box.”

Rapid DNA programs are not new. Other law enforcement agencies have used similar machines. But Louisiana is the first state in the country to work with the FBI to integrate it into the booking process. The machine analyzes samples against the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), a national database of DNA profiles.

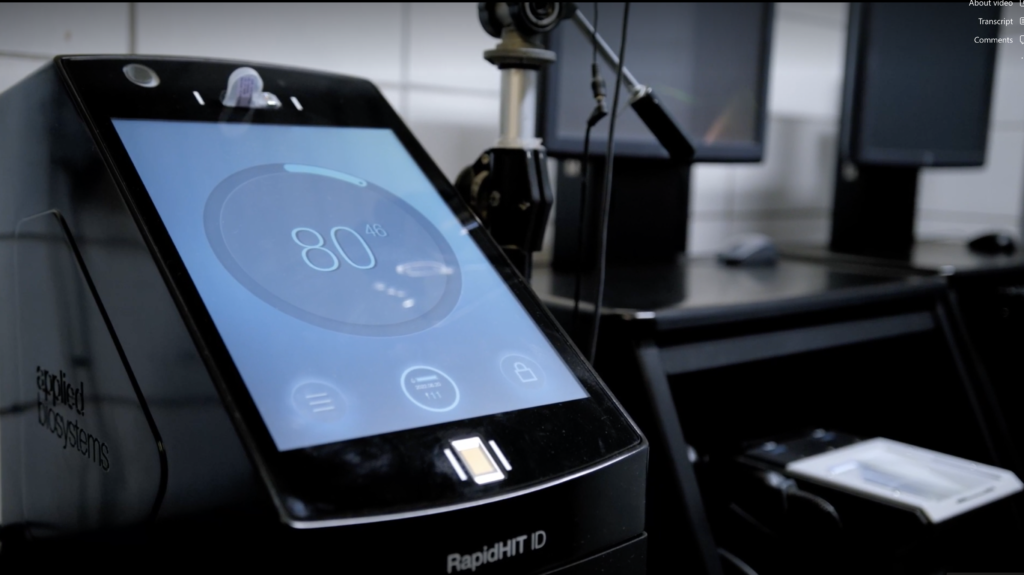

Typically, an officer in Louisiana would take a cheek swab sample during booking and send it to a lab, which might take weeks to return results. With these new machines, the size of a desktop computer, police officers can get that information on-site in less than 90 minutes.

A screenshot from a training video for police officers on how to properly use a “Rapid DNA” machine at the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Office. Image provided by EBRSO

“It’s the same [forensic] technologies that crime teams have been using for decades,” said Philip Simmers, a DNA analyst at Louisiana State Police Crime Lab. “Rapid DNA just takes the technology and miniaturizes it and makes it portable.”

Law enforcement officials tout the Rapid DNA technology as a big boost to investigative work. It can aid in arrests and potentially keep criminals from being unknowingly released. The speediness can also help lessen the burden of backlogs at crime labs.

“Fast information gets criminals off the street,” East Baton Rouge Sheriff Sid Gautreaux, III, said in a statement. These machines “strengthen our law enforcement, help with communications, and keep our community safe. The speed and efficiency of this is just unbelievable.”

The first Rapid DNA machine in Louisiana was installed at the East Baton Rouge Parish jail in August 2022.

In the last eight months, the Louisiana State Police report five people have been connected to previous crimes via Rapid DNA, including a 2013 homicide, a 2020 carjacking case that is being investigated by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, two burglaries, and the police officer shooting in the Baton Rouge area. The jail has since purchased a second machine.

The Louisiana State Police Crime Lab (LSPCL) expects to expand its use of Rapid DNA at booking to four police agencies across the state by the end of the year. As an added precaution, Louisiana continues to collect a second cheek swab sample that’s sent to LSPCL for DNA analysis.

Simmers, who described the technology as “a game changer,” said the machines can help identify arrestees wanted in connection with rapes, murders, kidnappings, terrorism, and other major crimes while they are still in police custody. He also sees the technology as an opportunity to improve the process of DNA collection and identification of “qualified arrestees,” including those arrested on suspicion of a felony or about 20 different misdemeanors as identified by state law.

“We have had success just from one booking agency. So we’re very optimistic that by expanding to more sites, we’re going to continue to see more successes from the program,” Simmers said.

As Rapid DNA grows, some concerns are raised

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 decided DNA collection practice was “like fingerprinting and photographing, a legitimate police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.”

But even so, there has been backlash from some criminal justice advocates, largely over how the technology could be misused.

“There are very few protections for Americans right now on DNA collection, and I think we all should be concerned about that because there is a very strong likelihood that people will be implicated for crimes that they didn’t commit purely based on a DNA sample,” said Jennifer Lynch, surveillance litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). “That risk increases when you have a technology like Rapid DNA that is not proven.”

Lynch pointed to a 2017 Swedish study that found issues with how crime scene DNA was tested on a Rapid DNA device, including risks of contamination and sample mix-up. A company spokesman for the manufacturer behind the device declined to comment on the study, according to reporting by the Los Angeles Times.

Lynch said she is concerned that Rapid DNA technology encourages the growth of government DNA databases. But even with things like the FBI’s standards for use at booking, she questions whether the rollout has proper oversight. In the meantime, for other uses, the FBI has only suggested best practices for use of Rapid DNA beyond the booking context, and there’s nothing obligating other agencies to follow those standards, she said.

“We could get to a place where all Americans end up in a DNA database, and it just sort of happens very slowly. And I don’t think we realize how that’s happening,” she said.

Other critics, like the American Civil Liberties Union, said the technology lacks safeguards and oversight over how Rapid DNA machines are designed and used in handling DNA, “some of our most sensitive information.”

“These machines are also being used by police in ways they aren’t intended for. They were designed to test samples taken from individuals for identification purposes, but local police departments are already deploying them on crime scene evidence, which is often far more complex,” the ACLU said in 2019.

Among its recommendations, the ACLU called for strict quality control and transparency, especially for communities to know how police officers intend to use the technology.

Currently, the FBI program will not allow the submission of unknown crime scene DNA from the Rapid DNA machines to the CODIS database. For now, only single-source samples can be checked for a hit.

“Since known reference samples are taken directly from an individual during booking station Rapid DNA analysis, we know there are sufficient amounts of DNA and that there are no mixed profiles that would require a human scientist to interpret,” said Douglas Hares, the FBI’s Rapid DNA implementation program adviser.

The agency doesn’t rule out crime scene DNA for the future. But “the technology needs to be enhanced a little bit before we can do that,” he said.

Both EFF and the ACLU also worry that the technology could exacerbate racially biased policing practices, including racial disparities in DNA collection. According to the ACLU, this is because “our criminal justice system disproportionately suspects, arrests, and convicts people of color — and collects DNA from them accordingly.”

While Lynch said “it’s impossible to put the genie back in the bottle on Rapid DNA,” she said, “we are at a place where we could place restrictions on the use of Rapid DNA,” noting the Department of Justice could curtail and put more restrictions on the funding to slow the growth of the technology.

How Louisiana became a national leader in Rapid DNA

Congress approved legislation to launch a Rapid DNA network in 2017. Signed by former President Donald Trump, the Rapid DNA Act of 2017 allowed the machines to connect to CODIS.

The FBI started a two-month pilot in 2020 in Louisiana, Florida, Arizona, and Texas and then authorized Louisiana to launch the first program in August 2022.

A key consideration was which states allow immediate DNA collection of arrestees at booking. Most states do not allow DNA collection until there is probable cause, or not at all, which makes them poor candidates for the FBI program.

The RapidHit Id system, left, is one of only two machines approved by the FBI for DNA identification at the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Office. Once a police officer takes a swab from an arrestee, it is placed in a cartridge that is then placed in the machine, right. A DNA profile can be completed within 90 minutes, and are searched against a national DNA database. Photos provided by EBRSO

“Louisiana really helped us to finalize the national booking standards and procedures that were required by the law,” Hares said. “They had successes early on that surprised me. I was not expecting so many hits that fast,” adding that the agency was excited that the technology sped up some investigations.

“To us, it was a success,” he added.

Some jurisdictions choose to purchase Rapid DNA machines and use them independently for investigations. But unless the program is authorized by the FBI, the machine can’t connect to the national database. Hares said the national standards are requirements to participate in the FBI’s program and not merely recommendations. The FBI has other protections in place, like fines that can be levied if there is an unauthorized disclosure of this data. Annual audits are also required both by the state agencies and the FBI to make sure the Rapid DNA booking system is running appropriately.

Hares said the FBI “hasn’t really seen inaccuracies,” and the instrument has a 90 percent success rate of producing a full profile for the analyzed samples, a similar level of accuracy as compared to traditional lab work.

Louisiana law has allowed officers to take DNA samples on arrestees at booking for more than two decades but would send them to a crime lab that often could not process samples fast enough.

“The volume was just so very great that it was hard to keep up with that pace,” said Joanie Brocato, who served at the LSPCL for almost 20 years as the DNA manager for forensic casework and CODIS. “We had improved the process as much as we could. We looked at the efficiencies of the lab, but we could still see gaps. We could still see samples being missed.”

Brocato said samples would face lag times in just making it to the laboratory. “So we really saw this as an opportunity to improve the process and close some of those gaps,” she said.

Brocato worked in the early stages of the FBI pilot and is now the clinical lab science department head at LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. For scientists like Brocato, it is important to ensure that the same level of quality that’s achieved in a lab can be met at a booking station.

“We got to see the instrument. We got to test the instrument. We had to make sure that we felt comfortable with the reproducibility of the results,” Brocato said, adding that vendors had worked for years to optimize the process. “We had to set up stringent training for the officers … to make sure everyone who would have access knows how to properly run the instrument.”

Brocato said the biggest hurdle was creating information infrastructure that included systems to collect, store and disseminate information, as well as designing processes to communicate with other agencies. “Everything needed to be automated and electronic,” she said.

“If we were going to move this instrument to a remote site, how were we going to get the data securely, safely, and protect it while being sent to the laboratory?” Brocato said. “The biggest thing was we just wanted to make sure that you couldn’t just randomly run a sample. It had to be linked to a direct fingerprint ID of an individual arrested, and in that setting, no one could openly access that data. But, we also had to make sure that we had the ability at any time to go in and audit the sites. For me, those were critical parts.”

The technology is also costly. Although grants are available from the Department of Justice, which Louisiana has acquired, each FBI-authorized Rapid DNA machine can cost around $200,000, and samples cost over $150 each.

How quickly can the Rapid DNA scale up?

The Louisiana State Police Crime Lab has already expanded its use of Rapid DNA to Livingston Parish and will add Ascension Parish and New Orleans by the end of 2023.

“This would be a major enhancement to solve and prevent crime and save police resources,” New Orleans City Council Vice President Helena Moreno said after she led a February delegation from New Orleans to tour the facility in Baton Rouge and lobby for a Rapid DNA at booking. “I certainly think it is something that we have to push for and fight for, particularly when it comes to the serial offenders, and whatever we can do to bring someone to justice quicker and to bring justice for victims faster.”

Moreno was among the city leaders who pushed for the technology in New Orleans following spikes in crime there. Compared to 2020, homicides in New Orleans are up 71 percent, shootings are up 52 percent, carjackings are up 14 percent, and armed robbery is up 20 percent, according to the city’s Metropolitan Crime Commission.

“I think this is no doubt the future,” Moreno told the NewsHour. “I feel very confident that all the safety protocols and privacy protocols will be in place. I actually don’t think it’s moved fast enough.”

But Moreno hopes the ever-improving DNA forensics around Rapid DNA could eventually be used for crime scene data to revolutionize modern crime-fighting even more.

“That’s something that myself and Baton Rouge are really advocating for: ‘How much more can we push to be on the forefront of utilization of rapid DNA?’ We’re not quite there yet, but I think we’re close,” Moreno said.

Hares stressed that the machines at booking are “another tool in the toolbelt” and “no one piece of evidence necessarily is going to be the thing that solves the crime.”

He pointed to a number of other challenges, too. Booking machines can be cost-prohibitive. State laws need to be updated to allow for DNA collection at booking. And there’s a need for national standards.

The FBI’s Rapid DNA Crime Scene Technology Advancement Task Group is also working with the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM) to ultimately create, test and approve expert systems for crime scene DNA samples from more than one individual. Hares authored a report and identified several major areas that must be addressed before considering the use of Rapid DNA in forensic casework.

But for the booking station Rapid DNA analysis, Hares said the FBI is ready to expand and meet the need.

As other states look to use new technology, he said, “we’re able to meet any of the demands.”