The relaunch of Windows on Arm has coincided with the arrival of Copilot+ PCs – devices that can execute Microsoft’s vision for the future of the Windows PC. Copilot+ PCs feature dedicated hardware that can run AI models on-device, unlocking new functionality ranging from generative AI-powered content creation to automatic image upscaling for games.

For now, Copilot+ PCs are exclusively powered by Qualcomm’s Arm-based Snapdragon X hardware platform, with over a dozen PC makers having already launched devices.

This renewed investment by Microsoft and partners marks a significant milestone for Windows on Arm, which previously has seen meager support. Previous-generation processors built using the Arm architecture were unable to compete with processors on the x86 architecture from Intel and AMD, while software compatibility was not robust enough for most users’ requirements.

For instance, 2012’s ill-fated Windows RT only supported software specifically built for Arm, leaving behind support for decades of Windows software that users still depended on. While Windows 10 improved the situation with support for emulation of x86 software, this did not extend to increasingly predominant 64-bit software. Meanwhile, support for graphics-reliant applications was limited, rendering PC gaming off limits on Arm devices.

Fast forward to 2024 and Microsoft and Qualcomm have promised Arm devices that offer greater power efficiency and performance than previous generation x86 processors from AMD and Intel.

Microsoft has also developed an improved translation layer, called Prism, to improve Windows on Arm’s compatibility with x86 software. Qualcomm is so confident in Prism’s capabilities that it assured game developers at GDC 2024 that most of their games should work without additional tweaking.

This is an ambitious claim, considering the huge library of PC games native to the x86 architecture –over 110,000 games have been published on Steam at the time of writing. For many, the PC platform is synonymous with backwards compatibility, as users invest in building up a library of games over generations of PC ownership.

Gaming remains a core weakness of Windows on Arm

Despite the big promises Qualcomm has made to game developers, gaming remains a core weakness of Windows on Arm, as compatibility with the huge library of Windows PC games remains patchy at best.

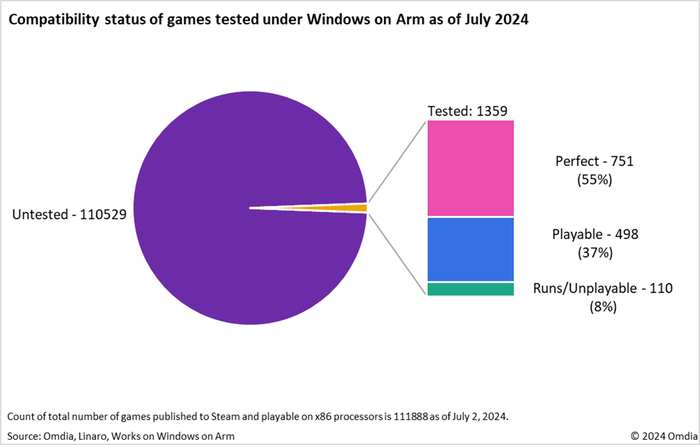

So far, just over 1,300 PC games have been independently tested for compatibility on Windows on Arm by the PC gaming community, which includes players and developers. Omdia analysis of this subset of tested games shows that barely half (55%) of games run smoothly without bugs or glitches (see Figure 1). That still leaves an large number of games that either fail to work or exhibit serious problems.

Figure 1: Around half currently tested titles exhibit issues on Windows on Arm

Source: Omdia, Linaro, Works on Windows on Arm

To make matters worse, popular multiplayer games such as League of Legends, Destiny 2, Fortnite, Apex Legends, and PUBG: Battlegrounds are currently unplayable via Windows on Arm due to incompatibility with anti-cheat software.

Another critical issue holding back robust support for gaming is Qualcomm’s nascent hardware. It is still early days for Qualcomm’s Adreno GPUs in the PC space. Its drivers are in an immature state and don’t allow its graphics hardware to fully interface with the graphical demands of PC games, posing a further challenge to compatibility and performance.

PC gaming does not have an immediate future on Arm

With a large swathe of publishers’ PC games catalogs left in various states of incompatibility, what can be done? The PC gaming landscape isn’t just defined by the publishers and developers releasing games for the Windows operating system, but the hardware those games run on, and the numerous distribution platforms from which games are sold.

First, the hardware: Following the relaunch of Windows on Arm in June 2024, Arm-based Windows devices accounted for just 0.05% of Steam users according to Valve’s Steam hardware survey. Until mass adoption occurs, games publishers are not incentivized to produce native versions of their software.

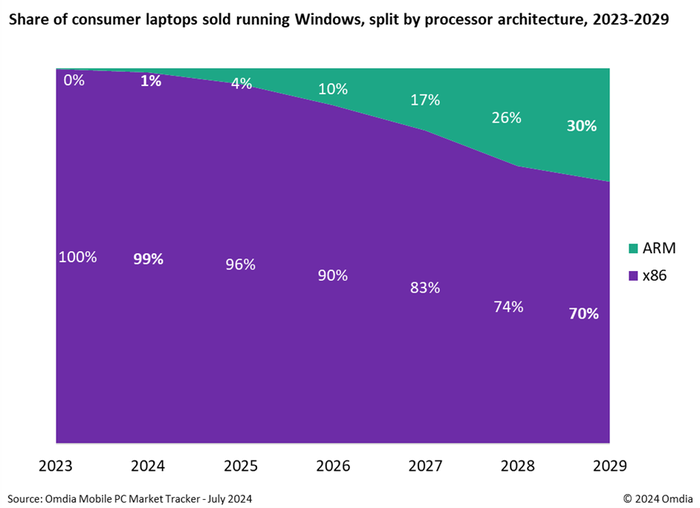

This is unlikely to change in the short term. Omdia’s Mobile PC Market Tracker estimates that Arm-based laptops will only account for just 1% of shipments of consumer laptops shipped with the Windows operating system in 2024 (see Figure 2). However, in the longer-term, this share is expected to grow to 30% by 2029.

Figure 2: Sales volumes of Arm-powered consumer laptops to remain low in the short term

Source: Omdia Mobile PC Market Tracker - July 2024

Secondly, PC games distribution: even if publishers were producing Arm-native versions of their games today, the vast majority release games via third-party distribution platforms. This creates its own set of issues.

Moreover, Microsoft doesn’t support local playback of Xbox PC games on Arm devices via the preinstalled Xbox app on Windows 11. Even more importantly, Steam, the world’s largest PC games distribution platform, is firmly focused on serving the existing x86 audience, including its own handheld gaming device, Steam Deck.

Publishers cannot distribute Arm versions of their software on Steam, and there is no indication that this will change. This in turn reduces publishers’ incentive to better support the currently small audience on Windows on Arm, reducing Steam’s incentive to support Arm devices.

The situation ultimately leaves game developers and publishers dependent on two key aspects to the Windows on Arm ecosystem that they do not control: Microsoft’s Prism translation layer and improvements made to Qualcomm’s graphics drivers.

Neither are quick fixes. In early 2024, Sarah Bond, President of Xbox, announced the formation of a team dedicated to forwards-compatibility of its games catalog that spans PC and console. Yet this is unlikely to be a task accomplished before 2026 at the earliest.

Meanwhile, Qualcomm’s graphics drivers are unlikely to reach a robust level of compatibility with PC games for several years. As a new entrant in this space, it will need to optimize its drivers on a per-game basis, which is time-consuming and expensive. Other hardware vendors such as Nvidia entering the Windows on Arm space could improve the situation with their mature graphics drivers, but Omdia does not anticipate this to occur until 2026.

PC gaming on Arm is ultimately faced with the classic chicken-and-egg situation. Without a sufficiently large and proven audience of players on Arm devices, both publishers and PC games distribution platforms have little incentive to support the Arm platform, putting the onus on companies such as Microsoft and Qualcomm to improve compatibility in a bid to foster developer adoption.

In the meantime, publishers and developers of PC games should focus on communicating what this means for their audience, utilizing social media channels and game store pages to inform players and potential buyers about what level of playability they should anticipate if they were using an Arm-based machine.

Despite Microsoft’s eagerness to push the Arm architecture at the center of its new Copilot+ PC vision, the reality is that dedicated PC gaming enthusiasts will continue to favor PCs powered by the x86 architecture. While a move to Arm promises users with lighter and more efficient PC hardware, the state of PC gaming on Arm has a lot of catching up to do as the developer ecosystem remains in infancy.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)