Books

‘Jaws 2’ – Diving into the Underrated Sequel’s Very Different Novelization

It took nearly five decades for it to happen, but the tide has turned for Jaws 2. Not everyone has budged on this divisive sequel, but general opinion is certainly kinder, if not more merciful. Excusing a rehashed plot — critic Gene Siskel said the film had “the same story as the original, the same island, the same stupid mayor, the same police chief, the same script…” — Jaws 2 is rather fun when met on its own simple terms. However, less simple is the novelization; the film and its companion read are like oil and water. While both versions reach the same destination in the end, the novelization’s story makes far more waves before getting on with its man-versus-shark climax.

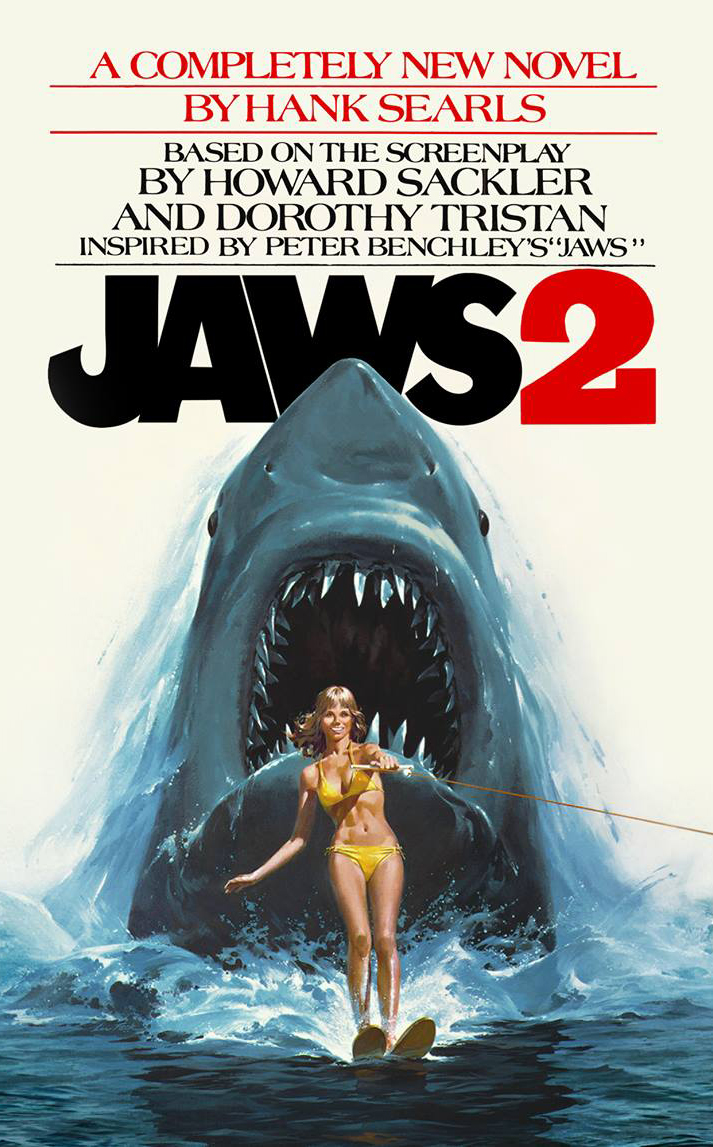

Jaws 2 is not labeled as much of a troubled production as its predecessor, but there were problems behind the scenes. Firing the director mid-stream surely counts as a big one; John D. Hancock was replaced with French filmmaker Jeannot Szwarc. Also, Jaws co-writer Carl Gottlieb returned to rewrite Howard Sackler’s script for the sequel, which had already been revised by Hancock’s wife, Dorothy Tristan. What the creative couple originally had in store for Jaws 2 was darker, much to the chagrin of Universal. Hence Hancock and Tristan’s departures. Hank Searls’ novelization states it is “based on a screenplay by Howard Sackler and Dorothy Tristan,” whereas in his book The Jaws Log, Gottlieb claims the “earlier Sackler material was the basis” for the tie-in. What’s more interesting is the “inspired by Peter Benchley’s Jaws” line on the novelization’s cover. This aspect is evident when Searls brings up Ellen’s affair with Hooper as well as Mayor Larry Vaughan’s connection to the mob. Both plot points are unique to Benchley’s novel.

The novelization gives a fair idea of what could have been Jaws 2 had Hancock stayed on as director. The book’s story does not come across as dark as fans have been led to believe, but it is more serious in tone — not to mention sinuous — than Szwarc’s film. A great difference early on is how Amity looks and feels a few years after the original shark attack (euphemized by locals as “The Troubles”). In the film, it seems as if everything, from the townsfolk to the economy, is unaffected by the tragedies of ‘75. Searls, on the other hand, paints Amity as a ghost town in progress. Tourism is down and money is hard to come by. The residents are visibly unhappy, with some more than others. Those who couldn’t sell off their properties and vacate during The Troubles are now left to deal with the aftermath.

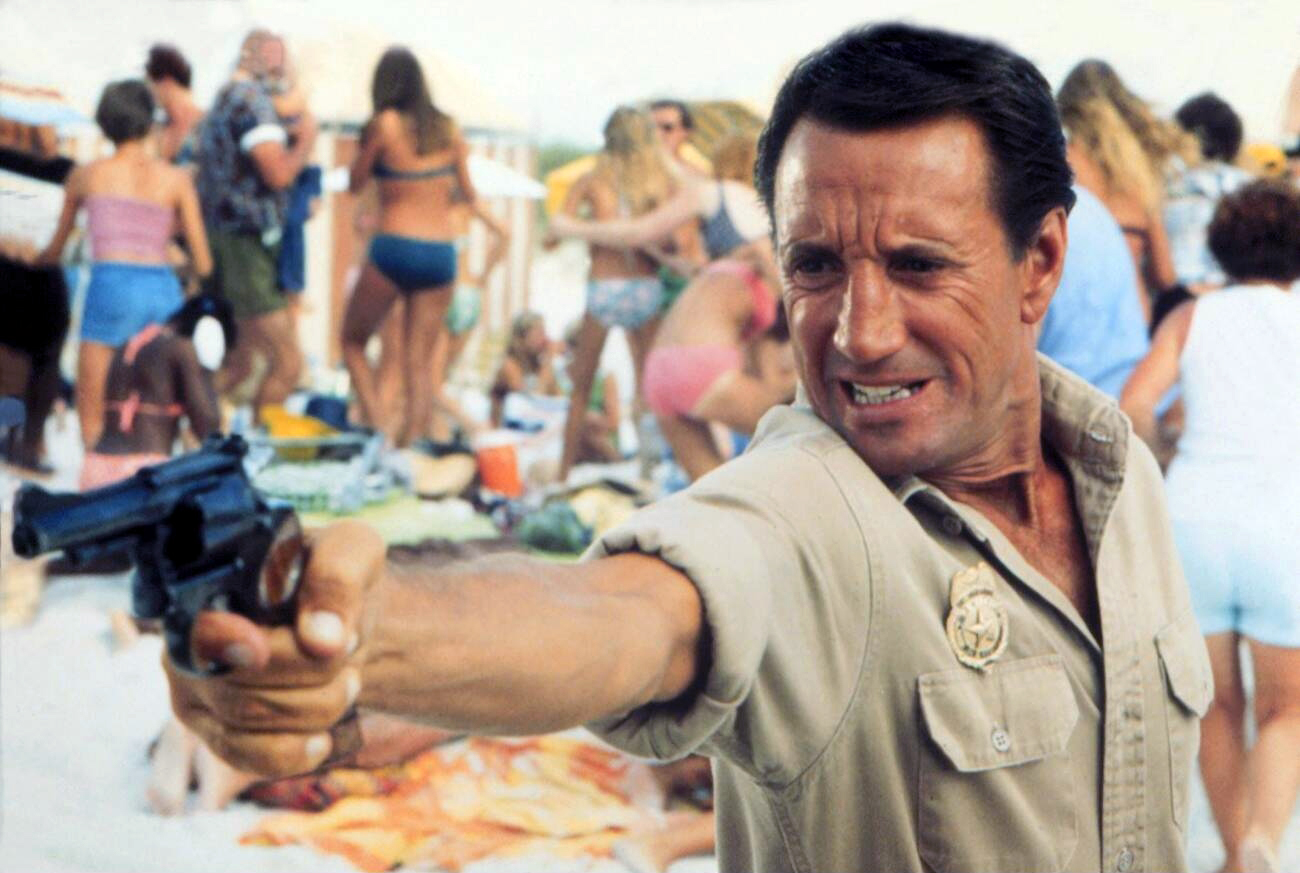

Image: As Martin Brody, Roy Scheider opens fire on the beach in Jaws 2.

It is said that Roy Scheider only came back to fulfill a three-picture deal with Universal (with Jaws 2 counting as two films) and to avoid having his character recast. Apparently, he was also not too pleased (or pleasant) after Szwarc signed on. Nevertheless, Scheider turned in an outstanding performance as the returning and now quietly anguished Martin Brody. Even in the film’s current form, there are still significant remnants of the chief’s psychological torment and pathos. Brody opening fire on what he thought to be the shark, as shocked beachgoers flee for their lives nearby, is an equally horrifying and sad moment in the film.

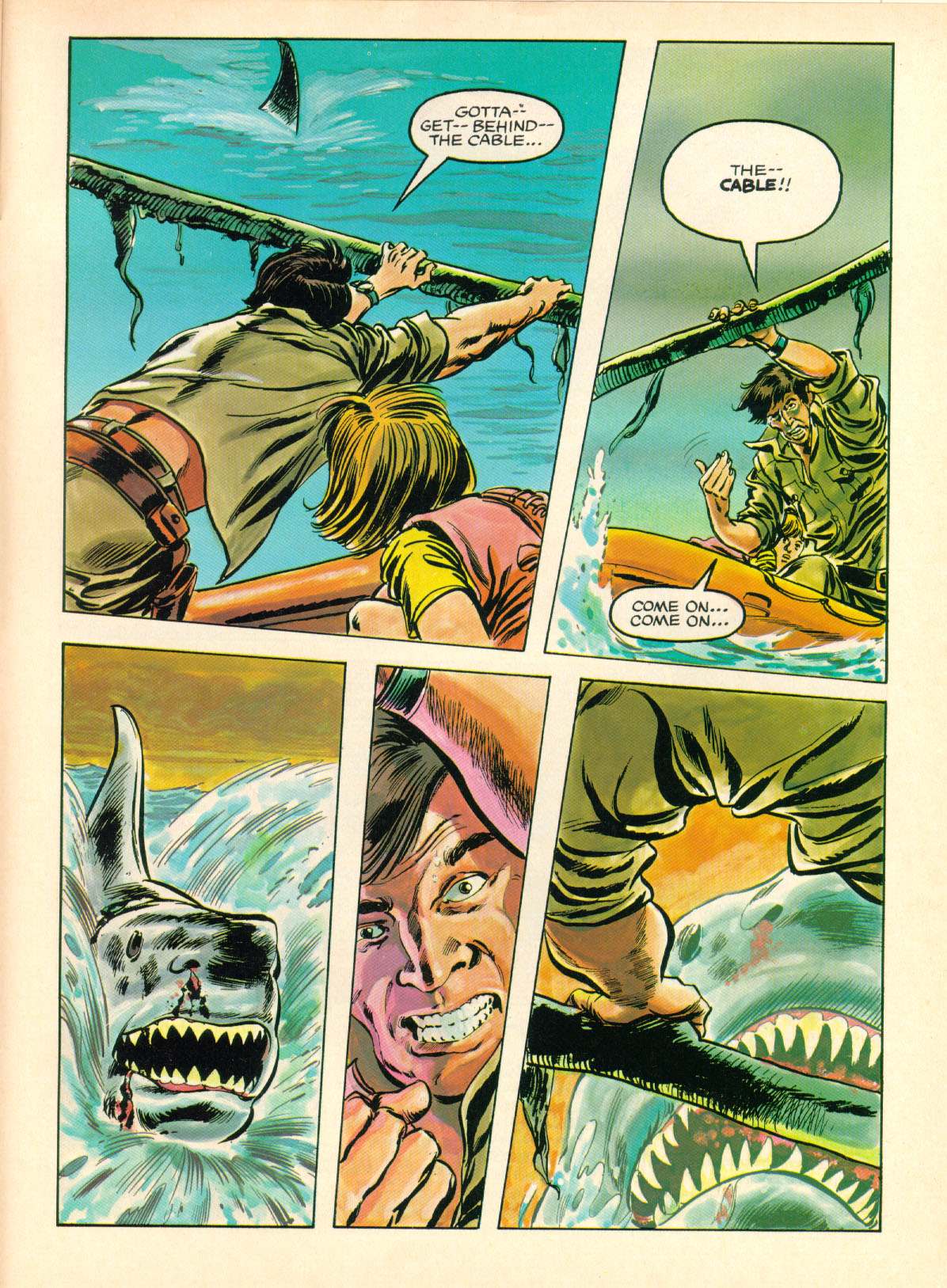

In a candid interview coupled with Marvel’s illustrated adaptation of Jaws 2, Szwarc said he had posted the message “subtlety is the picture’s worst enemy” above the editor’s bench. So that particular beach scene and others are, indeed, not at all subtle, but neither are the actions of Brody’s literary counterpart. Such as, his pinning the recent deaths on Jepps, a vacationing cop from Flushing. The trigger-happy drunk’s actual crimes are breaking gun laws and killing noisy seals. Regardless, it’s easier for Brody to blame this annoying out-of-towner than conceive there being another great white in Amity. Those seals, by the way, would normally stay off the shore unless there was something driving them out of the ocean…

Brody’s suspicions about there being another shark surface early on in the film. For too long he is the only one who will even give the theory any serious thought, in fact. The gaslighting of Brody, be it intentional or otherwise, is frustrating, especially when considering the character is suffering from PTSD. It was the ‘70s though, so there was no intelligible name for what Brody was going through. Not yet, at least. Instead, the film delivers a compelling (and, yes, unsubtle) depiction of a person who, essentially, returned from war and watched a fellow soldier die before his very eyes. None of that trauma registers on the Martin Brody first shown in Jaws 2. Which, of course, was the result of studio interference. Even after all that effort to make an entertaining and not depressing sequel, the finished product still has its somber parts.

Image: A page from Marvel’s illustrated adaptation of Jaws 2.

How Brody handles his internal turmoil in the novelization is different, largely because he is always thinking about the shark. Even before there is either an inkling or confirmation of the new one. It doesn’t help that his oldest son, Mike, hasn’t been the same since The Troubles. The boy has inherited his father’s fear of the ocean as well as developed his own. Being kept in the dark about the second shark is also detrimental to Brody’s psyche; the local druggist and photo developer could have alleviated that self-doubt had he told Brody what he found on the dead scuba diver’s undeveloped roll of film. Instead, Nate Starbuck kept this visual proof of the shark to himself. His reasons for doing so are connected to the other pressing subplot in the novelization.

While the film makes a relatively straight line for its ending, Searls takes various and lengthy detours along the way. The greatest would be the development of a casino to help stimulate the local economy and bring back tourists. Brody incriminating Jepps inadvertently lands him smack dab in the middle of the shady casino deal, which is being funded with mafia money. A notorious mob boss from Queens, Moscotti, puts a target on Brody’s head (and his family) so long as the chief refuses to drop the charges against Jepps. In the meantime, the navy gets mixed up in the Amity horror after one of their helicopters crashes in the bay and its pilots go missing. A lesser subplot is the baby seal, named Sammy by Brody’s other son Sean, who the Brodys take in after he was wounded by Jepps. Eventually, and as expected, all roads lead back to the shark.

In either telling of Jaws 2, the shark is a near unstoppable killing machine, although less of a mindless one in the novelization. The film suggests this shark is looking for payback — Searls’ adaptation of Jaws: The Revenge clarifies this with a supernatural explanation — yet in the book, the shark is acting on her maternal instinct. Pregnant with multiple pups, the voracious mother-to-be was, in fact, impregnated by the previous maneater of Amity. Her desire to now find her offspring a safe home includes a body count. And perhaps as a reflection of the times, the author turns the shark and other animals’ scenes into miniature wildlife studies; readers are treated to small bits of infotainment as the story switches to the perspective of not only the killer shark, but also the seals and a navy-trained dolphin. The novelization doesn’t hold back on the scientific details, however weird as it may sound at times. One line sure to grab everyone’s attention: “There, passive and supine, she had received both of his yard-long, salami-shaped claspers into her twin vents.”

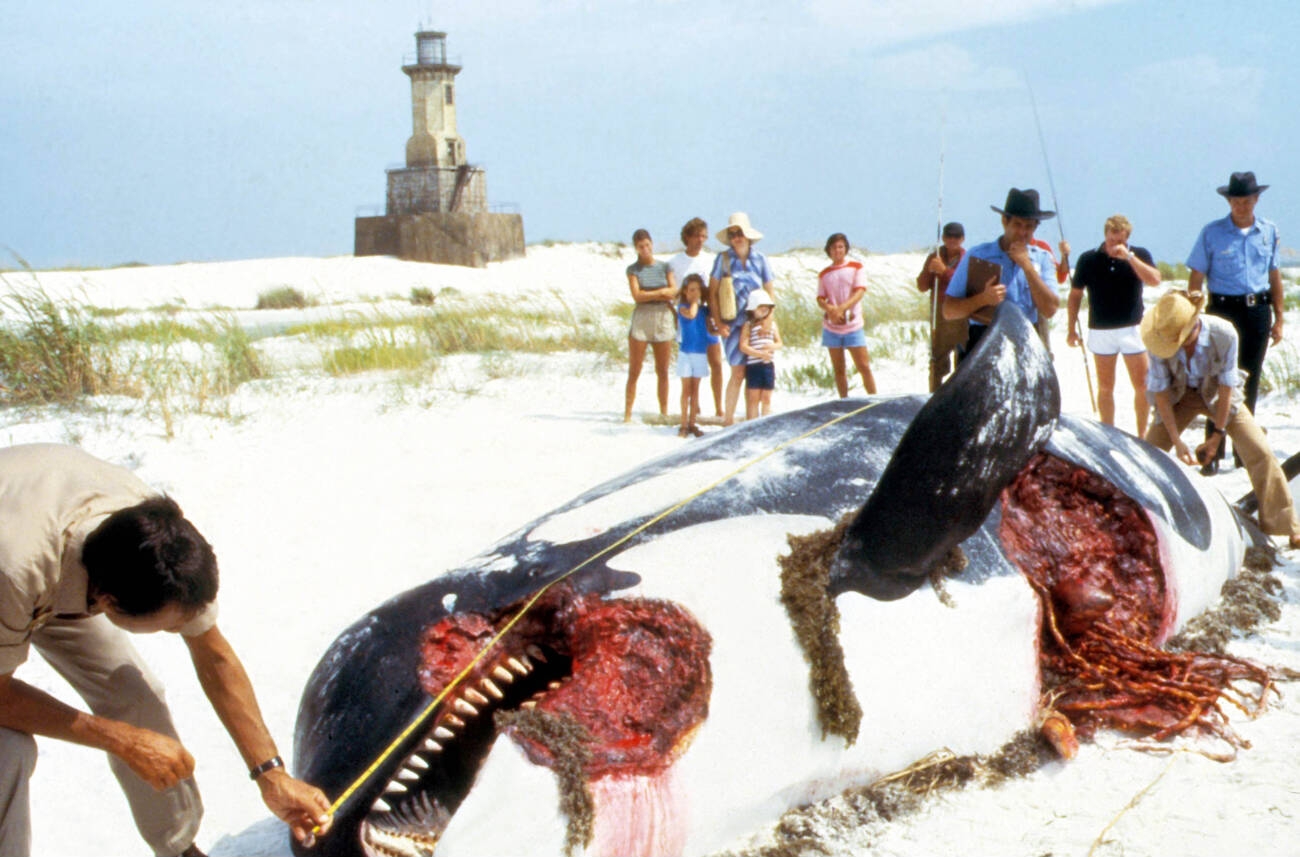

Image: Roy Scheider’s character, Martin Brody, measures the bitemark on the orca in Jaws 2.

Up until the third act, the novelization is hard to put down. That’s saying a lot, considering the overall shark action borders on underwhelming. There is, after all, more to the story here than a fish’s killing spree. Ultimately though, Szwarc’s Jaws 2 has the more satisfying finale. Steven Spielberg’s film benefitted from delaying the shark’s appearance, whereas the sequel’s director saw no need for mystery. The original film’s reveal was lightning in a bottle. So toward the end, Jaws 2 transforms into a cinematic theme park ride where imagination isn’t required. The slasher-at-sea scenario is at full throttle as the villain — wearing her facial burn like a killer would wear their mask — picks off teen chum and even a pesky helicopter. And that’s before a wiry, go-for-broke Brody fries up some great white in the sequel’s cathartic conclusion. That sort of over-the-top finisher is better seen than read.

It would be a shame to let this other version of Jaws 2 float out to sea and never be heard from again. On top of capturing the quotidian parts of Amity life and learning what makes Brody tick, Hank Searls drew up persuasive plot threads that make this novelization unlike anything in the film franchise. If the Jaws brand is ever resurrected for the screen, small or big, it wouldn’t hurt to revisit this shark tale for inspiration.

Image: The cover of Hank Searls’ novelization for Jaws 2.

Books

‘Disturbing Behavior’ – Revisiting the Teen Horror Movie 26 Years Later

While Scream set off a new slasher cycle in the late 1990s, MGM delivered something different with Disturbing Behavior. A fitting choice considering the film’s themes. Ultimately, though, this ‘98 teen chiller landed a bit more in the science-fiction bin than straight, undiluted horror; one by one, a town’s troubled youths endure sinister, personality-warping makeovers to make them better fit into society. That sort of genre pitch, when coupled with up-and-coming young actors like Katie Holmes and James Marsden, should have been enough to draw in the target demo. Yet the studio and the director, David Nutter, didn’t see eye to eye on things, resulting in one of the most troubled horror productions of that decade.

Scott Rosenberg’s screenplay for Disturbing Behavior was written a few years before Scream was released, and it was nearly produced by New Line Cinema before plans changed. Luckily for Rosenberg, he was allowed to shop his work around elsewhere. Once the project was picked up by MGM, Nutter then signed on after having mainly worked in television and only having one feature to his name; he directed a good deal of episodes during the early seasons of The X-Files. That greater part of his résumé likely landed him Disturbing Behavior. After all, the producers wanted the film to be like “X-Files for teenagers.”

Despite comparisons to The Stepford Wives, this youth-oriented reimagining does not have its characters being replaced by robots. On the contrary, the pubescent prey of a Northwestern town’s nefarious scheme are simply “upgraded.” Bruce Greenwood’s creepy character, a visiting school psychologist named Dr. Caldicott, is the mastermind behind the teenagers’ tinkering. His unique process involves the “regulation of endocrinologic surges;” unlike the film, John Whitman’s tie-in novelization brings up the doctor’s scientific methodology in slightly more detail. In fact, a small but not insignificant amount of what MGM left on the cutting room floor can be found in this literary companion.

Image: Katie Holmes, James Marsden, and Nick Stahl in Disturbing Behavior.

As it is now known, Disturbing Behavior experienced a brutal hack job prior to its theatrical release (and tanking). Negative remarks during test audience screenings spurred edits, much to the chagrin of Nutter. However, when the first set of changes did not produce a higher score at a subsequent test screening, the frustrated and desperate MGM took over and had the studio’s then vice president of production editing, George Folsey Jr., handle the final revision. What had already been cut down to a 95-minute film was then reduced to a 75-minute (minus credits) shell of Nutter’s vision. The outspoken director blamed much of the film’s failure on MGM’s former president Michael Nathanson along with his reliance on research from the National Research Group (NRG). Nutter thought the requested edits he made himself were valid, yet he found “MGM’s didn’t make sense at all.”

Circling back to the novelization, Disturbing Behavior’s biggest excision involved the protagonist of Steve Clark (Marsden) and his dead older brother, Allen (played by Ethan Embry on screen). This YA-sized book, which runs a tad under 190 pages with a photo section included, does not gloss over the distressing particulars of Allen’s death. Whereas the theatrical cut of the film momentarily mentions the origin of Steve’s dejection as well as the motivation for his perseverance. Test audiences did not like the fuller, tragic backstory of Allen, who died of suicide (along with his girlfriend), so Nutter pared down that narrative element to its most key parts. In doing so, though, Steve lost a fair share of his character arc. Even Rachel’s (Holmes) own vocal aspirations to get out of Cradle Bay, escape poverty, and go to college had been muted in favor of a more streamlined, commercial film.

Nutter told Fangoria back in 1998: “If you build it, they will come.” The “it” the director was referring to, of course, being a smart teen horror film. “You have to respect their intelligence, and they’ll respect you.” Sadly, MGM was on a different page. The studio did not seem too concerned by the watering down of the film’s characters and story, seeing as it just wanted a “Scream-style teen shocker” and for Nutter to get straight to the “fright beats.”

Image: Crystal Cass in Disturbing Behavior.

In the end, Disturbing Behavior comes out looking like an expensive episode of The X-Files. Having been shot in Vancouver and sharing actors and crew only reinforces that opinion. Even so, it remains a fairly attractive and nostalgic piece of late ’90s horror. No amount of overediting can erase that. Marsden, Holmes, and their co-stars, particularly Nick Stahl, also speak the punchy, stylized dialogue with “razor” credibility. And the brainwashed victims steal the show here, with their “hard-on” glitch fits coming across as more menacing and unsettling after being juxtaposed with clean-cut presentations.

There is no mistaking the cautionary tale quality to this film. The concept of a society suppressing people’s individuality is timeless, as is the danger of conforming. Yet as Disturbing Behavior demonstrates with jarring effect, controlling identity and limiting freedom has its adverse consequences. So while the thematic material here is executed in the most unsubtle manner, it still serves as an important lesson for every generation.

Nutter has since described his first major feature as the “worst experience” of his life; back then he was even tempted to remove his name from the project. Nutter’s negative reaction to the studio interference is certainly valid, yet what survived is still rather watchable and entertaining. And supplementing the theatrical cut are unofficial restorations with some deleted footage reinserted. This includes the original conclusion that test audiences disliked �� on account of Stahl’s character’s fate — and the whole messy story of Steven’s brother’s death. Nevertheless, cult fans of Disturbing Behavior would still prefer a bona fide director’s cut. One that not only gives the film a better semblance of what Nutter envisioned pre-MGM’s meddling, but also helps redeem it after years of harsh criticism.

Image: James Marsden’s character Steve with the Blue Ribbons in Disturbing Behavior.

You must be logged in to post a comment.